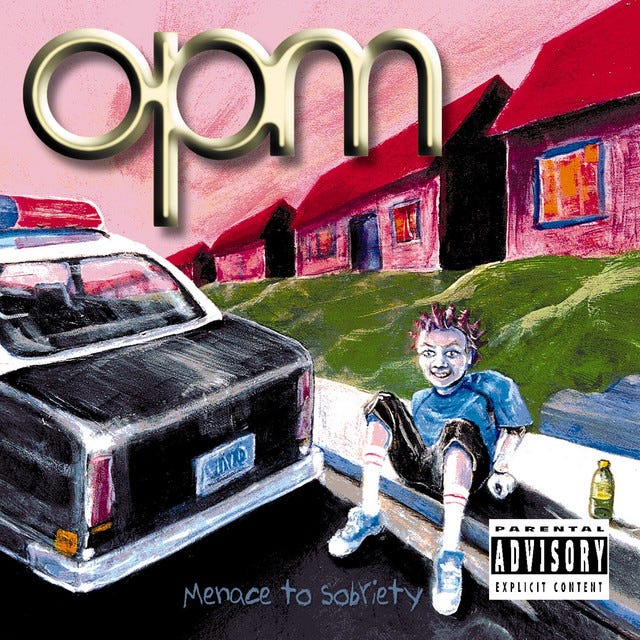

Back in the old days, I used to listen to a CD by OPM that included the interlude, “Rage Against the Coke Machine.” In this throwaway track by the band behind “Heaven Is a Halfpipe,” a guy in the band tries to get a soda from a vending machine. But the machine keeps rejecting his dollar. He starts cursing. We hear him kick the vending machine a couple times. He smooths out the dollar.

Finally the vending machine takes the dollar, but it refuses to give him his Coke. Now he starts smashing buttons. “First you take an hour to taking the fucking dollar, now you ain’t giving me my shit,” he says. He starts yelling at the top of his lungs. Glass smashes. He beats the hell out of the vending machine, giving us all the collective relief of having won against the machine, this time at least.

We’ve all felt it: the machine always wins. It never loses its cool. And these days, as writers, people are starting to worry the machines aren’t just standing in the way of our soda pop. They’re doing our jobs. They’re actively pushing us out of the way.

That’s the worry, at least, that I hear hovering around the use of generative AI. First writers were frustrated, reasonably, that ChatGPT was trained using copyrighted texts by authors who never agree to it. This question has held sway to the extent that a book I recently started reading, Arctic Play by Mita Mahato, says on its copyright page,

Without in any way limiting the author’s and publisher’s exclusive rights under copyright, any use of this publication to “train” or develop generative artificial intelligence (AI) technologies and machine learning language models is expressly prohibited.

Even more worryingly, as AI grows smarter and comes into wider use, writers are looking at the possibility of AI replacing us. The Twitter uproar (really a willfull misunderstanding) around Lillian Yvonne-Bertram’s A Black Story May Contain Sensitive Content hinged, I think, on the anxiety that machines might be able to create better art than us. Now, some literary magazines ask submitters to identify whether they’ve used or engaged with generative AI in their writing.

But here’s the thing: AI actually can’t make better art than us. It can follow formulas, invent new storylines, and provide an emotionally satisfying experience to the reader. What it can’t do is anything meaningfully new. Anything that originates in the world—outside of the purview of the texts that have taught AI—is unavailable to the machines that “do” writing.

I find this fact encouraging. It forces us to consider what we carry with us that no one else carries, including the machine. What do we, personally, have to contribute? What can we say that no one else can say? What sentences can only you write?

That’s what AI helps us come face to face with. When you find the answers to those questions, you’ve found the thing that you need to write .

This prompt grows from the conviction that our most meaningful writing cannot be replicated. I originally did a version of this prompt on the very first day of my Fiction Writing I class this fall. I was following upon my colleague Christopher Grobe’s article in The Chronicle of Higher Education, “Why I’m Not Scared of ChatGPT.” Grobe describes doing an exercise with his students in which he encouraged them to use ChatGPT to answer the prompts he had given them for their essays. Spoiler alert: ChatGPT was not that good at it.

I wanted my students, too, to see the limitations of generative AI. I wanted this prompt to be a window into what they were capable of, a view into their own contributions as writers.

As a class, we developed a prompt. ChatGPT wrote in response to it. The story was funny—we had given it a prompt about a small, furry animal who was ambitious in the culinary field, because we weren’t taking this too seriously—and it hit all the right notes. But what it didn’t have was spirit. It was only as weird as our prompt. And, at least for me, it didn’t have that deep core thing that I want when I read: a sense of the true idiosyncrasy, the unresolvedness, that a person brings to the page.

So here’s your prompt:

Choose a subject you’ve been wanting to write about for a long time, but haven’t found a way to write about yet.

Choose a genre: Fiction? Creative nonfiction? Poetry? Choose a word count too.

Write a prompt for ChatGPT that honestly tries to get the best possible response. Aim for what you want your piece of writing to look like. You might have to give multiple prompts, experiment with word counts, and name influences. Try to get the result as close as you can to something good.

When the piece is “finished,” read it slowly. On paper or in your head, take note of everything the piece does not do that you want your piece to do. What is this piece missing, not just in terms of content but in terms of style? How does it fail to communicate in the ways you want to communicate?

By this point in the process, you may be relatively worked up, perhaps even annoyed. Seeing how AI messes with a subject that means a lot to you hopefully raises some of that “Rage Against the Coke Machine” energy. Tune into this energy: What is it telling you about what your writing needs? What is still unsaid? How do you need to speak?

Now, write. Write from your own heart, leaving the inadequacies of AI behind but preserving your experience of reading it and being unsatisfied with what it produced. If you want, you can write in direct response to ChatGPT’s assumptions and tendencies. You can turn its phrases into opposites, or erase its lines into poems. You can describe the process of trying this prompt.

In the end, aim for a finished piece that you wrote, responding to the prompt you gave Chat GPT. Forgive the machine. It doesn’t know what you know.

I hope this prompt holds some magic for you! I believe every new complication in the writing life can be an opportunity: a way to encounter the uniqueness of our contribution.

AI is just one of those complications. The end goal is always what you can do, the writing practice that brings you home.