Prompt: Another view of Mount Fuji

Because the relationships between parts in Hiroshige's woodblock prints teach us the magic of juxtaposition

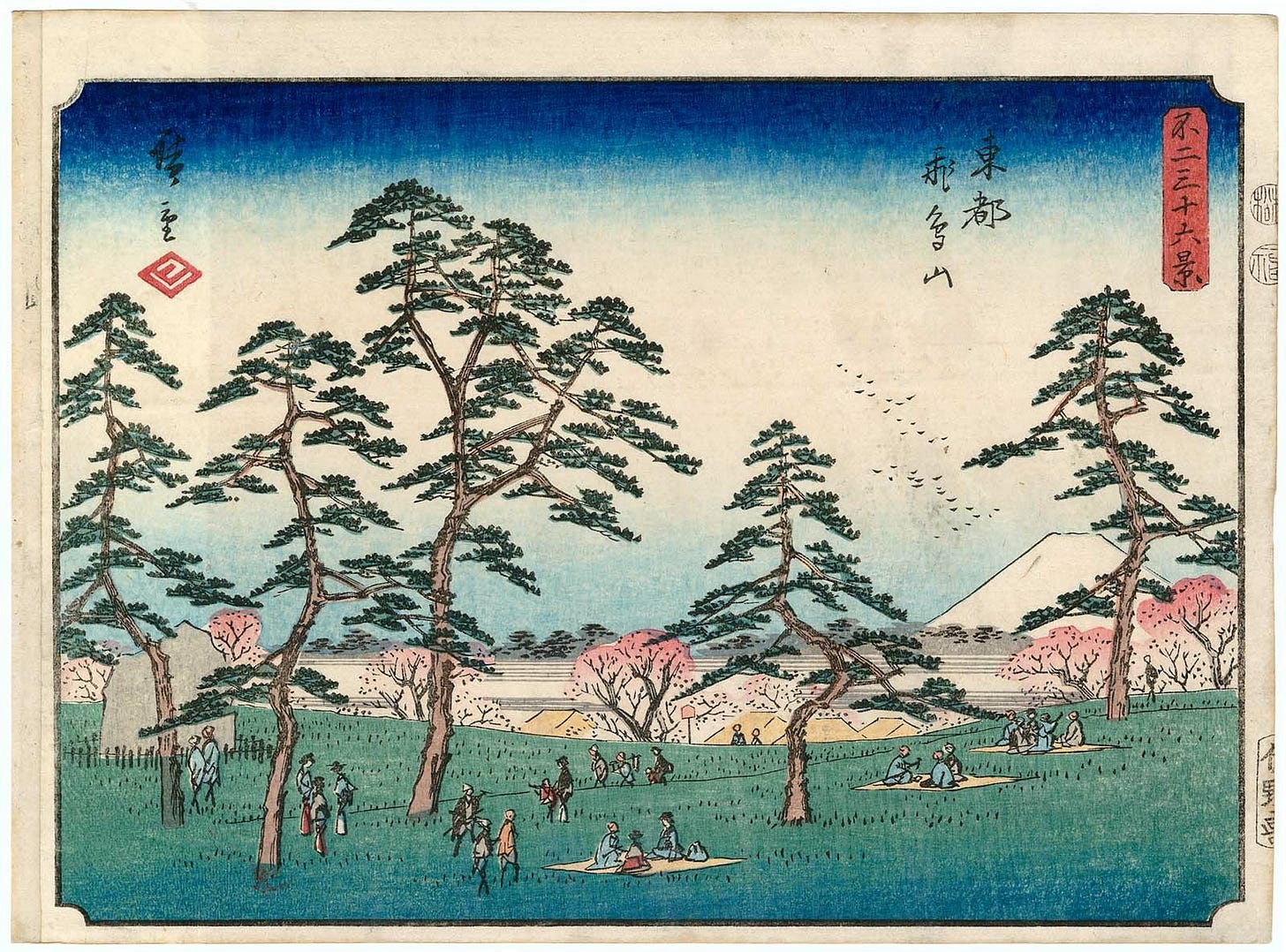

So I’ve been doing this thing where every time I come into my office at Amherst College, I open up to a new page of Hiroshige’s thirty-six views of Mount Fuji and look at it for a minute. I look at the landscapes and how they interact with the iconic mountain in the background. I look at the small people in the pictures and how they move across the print. I look at the water, or the grass, or the hills, and I think about the power things have when they are related to other things, and then I think about the fact that these relationships between things tell a story about living.

With the above print, for example, I might reflect on how the flatness of the landscape in the foreground exists most completely in relation to the giant angled mountain that takes up most of the sky. This might give me a feeling for the gentleness of everyday life, while at the same time the monumental nature of our presence on earth looms above us. But even that monumentalness is, somehow, gentle.

With this next print, I might reflect on how, despite the central presence of Mount Fuji in the background on the print, the real immediacy comes from the hole in the tree in the foreground, which frames nothing but the sky and the edges of blossoms. All of these prints are about perspective, but this one in particular reminds me that our nearness to what we experience frames our attention, and that there is plenty of beauty even in the smallness of that perspective.

I’ve been really inspired by looking at these thirty-six prints slowly, one each day, and I want to share a prompt that draws on the dynamic arrangement of each of them. Your writing, too can make use of the dynamic relationship between narrative/stylistic elements in order to help living textures arise.

So here’s your prompt:

Navigate to Hiroshige’s thirty-six views of Mount Fuji, the classic series of woodblock prints originally published in 1852.

Click on one that gets your attention, or that you feel intimately drawn to. Don’t overthink this. Follow your intuition toward the image that calls out to you today.

Look at it quietly for at least one minute.

Now, use the elements of the print to construct a writing prompt for yourself in your chosen genre. Allow mountains to become elements of narrative structure, stanzas, or characters in your story. Allow oceans, hills, and woods to become forces of desire, recurrent images, or discrete events. Then place each of these elements in relation to each other in a way that echoes the woodblock print you have chosen.

This prompt probably won’t make perfect sense at first! I’m going to give you some examples that will help you understand what I am asking you to do.

Example 1: Let’s say you want to write a short story in response to the first print I mentioned, “Fuji Marsh in Suruga Province.” After looking at the print for a minute, you might decide to write a short story in which an ostensibly calm, flat narrative style (like the marshes in the foreground) is haunted by a large but benevolent force that blocks out the story’s sky but can’t be grasped in its completeness (like Mount Fuji). As you write, introduce characters that echo but do not perfectly mimic that large and mysterious force (like the minor mountains in front of of Mount Fuji). Eventually, you might even add a narrative complication that draws on the birds or clouds at the top left of the print.

Example 2: Let’s say you want to write a poem. After looking at the print “Asuka Hill in Edo,” you could construct a five-stanza poem (for the five trees in the foreground) with the number of lines determined by the branches on the trees (six for the first tree on the left, and so on). Allow this poem to be highly populated by crowds of proper nouns (like the people who sit and walk in the field) while also being spacious and airy, like the view. If you need inspiration for the content of your poem, consider drawing on a dwelling space that means something to you, even if it is just at the edge of your view (like the village down below).

From these examples, you’ll see that how you interpret the elements of each image is up to you. But the fundamental structures that are animating your writing—the relation of each element to the other—should be determined by the woodblock print you choose. This deep, textured relationship between things is one of the most energetic lessons I learn from Hiroshige’s prints: if we place things in relation to one another with thoughtfulness, it is the relationship, even more than the things themselves, that comes alive.

A final note of advice: if you get stuck, go back to the print. You will find something there for you that you hadn’t seen, or that you hadn’t seen in the same way. Let the surprise of returning—the magic of approaching the same print over and over—remind you of the surprise that is possible in your writing. We’ve never written too far to add a wrinkle, a new relationship, a subtle revelation.