Two Questions with Kelly Krumrie

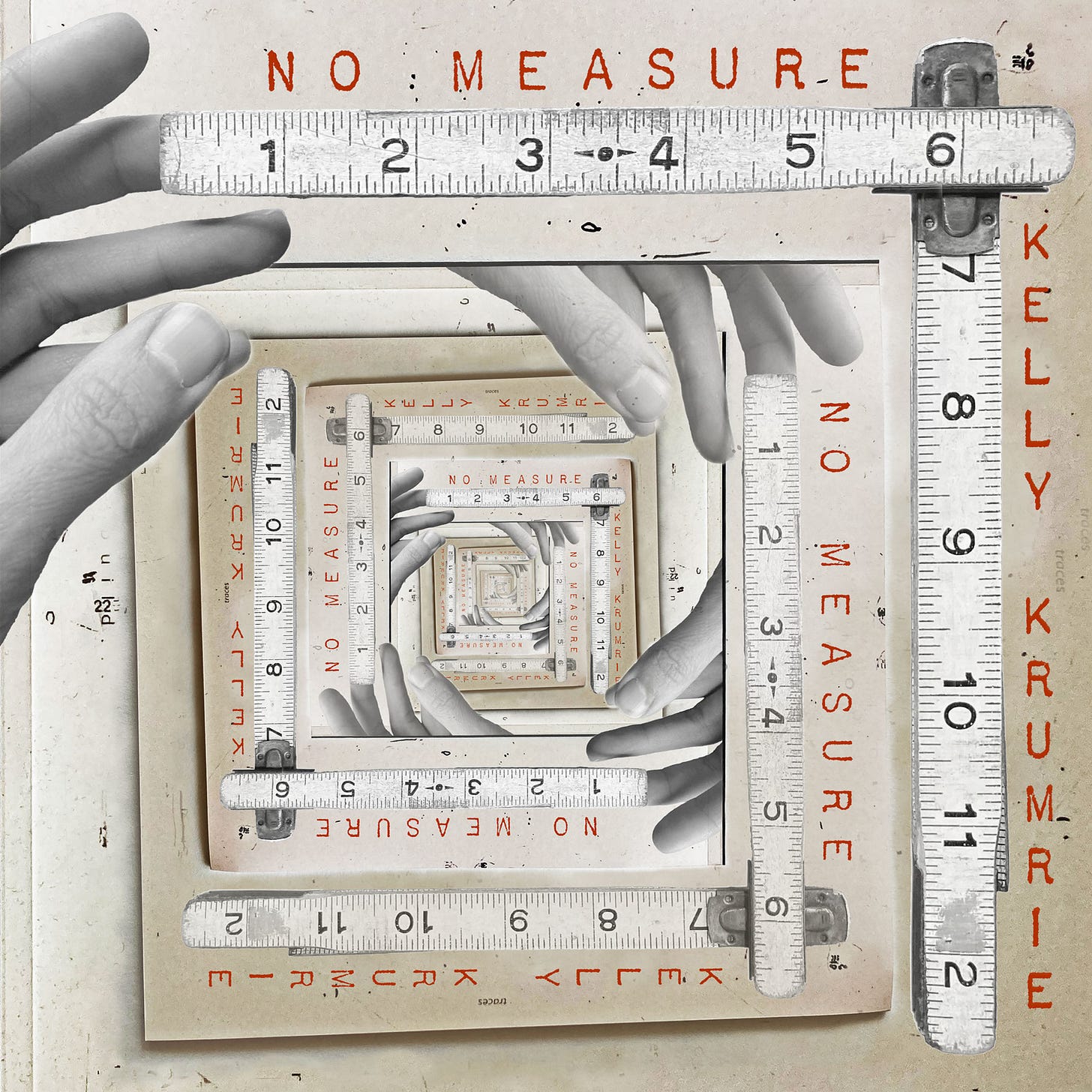

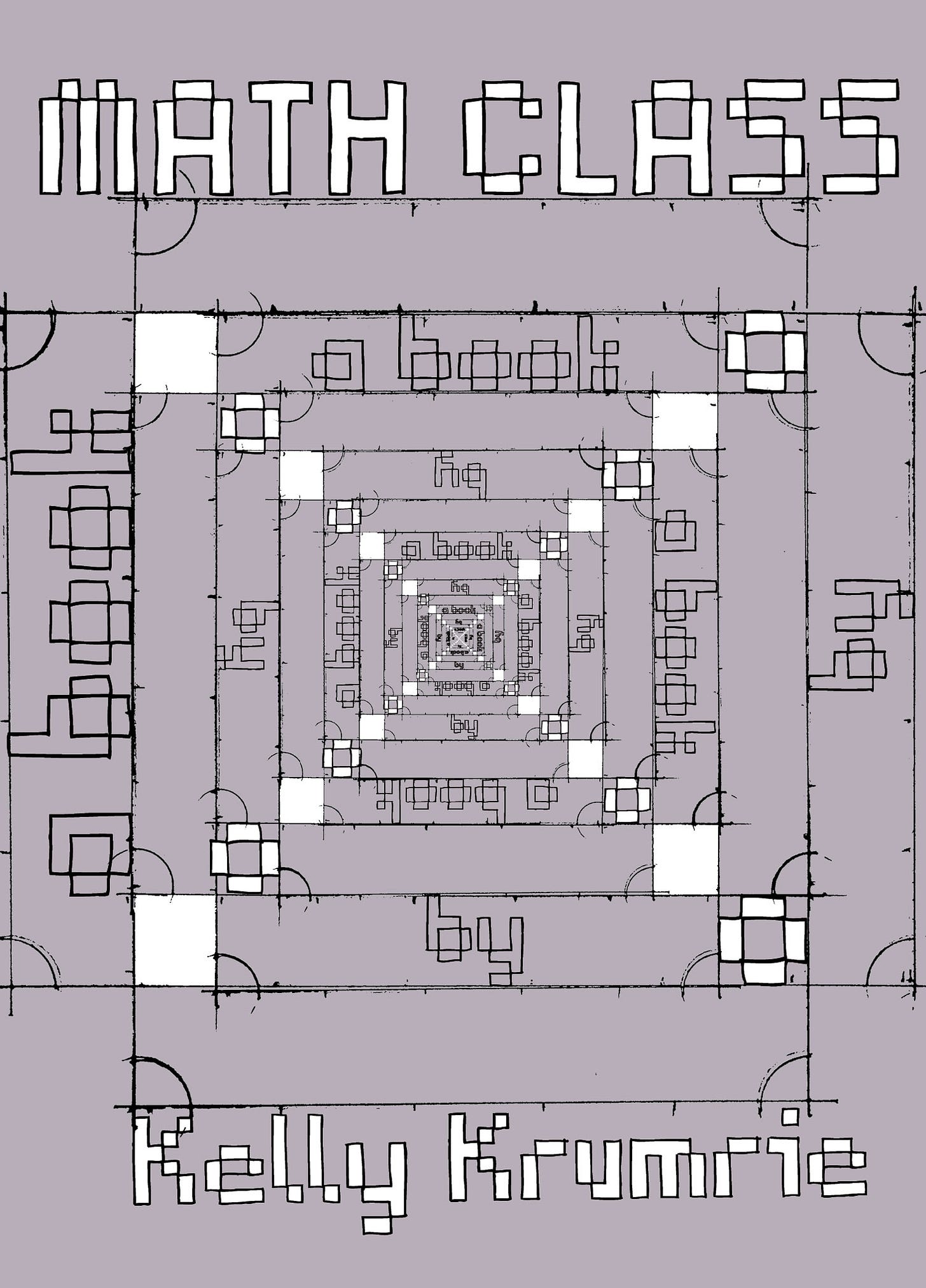

Author of No Measure (Calamari Archive, 2024) and Math Class (Calamari Archive, 2022)

Kelly Krumrie and I have crossed paths both knowingly and unknowingly: we both grew up in Cincinnati, for one thing, going to rival schools across town. Later on, we met for real at University of Denver, where we were both working on our PhDs in creative writing. I have always been moved by Kelly’s sense of purpose in her writing, its angularity and solidity, and at the same time its expansive sense of play.

Her first book, Math Class (Calamari Archive, 2022), incorporated quotes and concepts from a wealth of mathematical texts into a collection of short stories (you could sometimes call them poetic vignettes) that represent the life of Jo, alongside other friends, at the Catholic school she attends. I liked the way Mark Tardi describes the book in a review in Full Stop:

There’s a quantum or even fractal layering between the vignettes, toggling between a micro-scale where you can practically smell the dust bunnies in the school library and a wider, occasionally oneiric, perspectivism of the characters or environs. Added to that are various mathematical sketches interspersed throughout the book: coordinate grids, matrices, topology, physics problems. It’s almost as if, at times, reading can be fused with wandering through an art gallery.

Kelly’s new book, No Measure, was just released in October from Calamari Archive. It’s SO NEW I haven’t even had the chance to read it yet, but electric excerpts can be found in Harp & Altar, DIAGRAM, and new_sinews. And here’s a great blurb about the book from Amy Catanzano:

No Measure is a book of pithy mathematical seduction. Through an exploration of conventionally measurable systems (vanishing points and lines, geometries and grids), Kelly Krumrie’s visually compelling account of the deception of perceptual space challenges the very notion of absolute visibility and measure.

As a person obsessed with the limitations of measurement and how it nonetheless defines the bodies we live in and among, No Measure is at the top of my reading list for the coming months. Correspondingly, I was eager to hear Kelly give an account of her creative practice across these two books and beyond.

The Interview

One thing I've always been so impressed about with your fiction is its weaving in and out of source texts, ideas, and theories that give shape to your writing, sometimes in unseen ways. Having seen a little of your process, I remember the stacks of books that precede/accompany so much of what you write—I always thought it was so cool how patient you were when allowing your own writing to arrive in the midst of these other texts, and how fluid and interest-based your process of research and reading is. How do you think of the relation of your writing to the texts that are behind, beneath, and through it? How do you inhabit the practice itself of weaving them into what you do (if weaving is even the right metaphor)?

Kelly Krumrie: The process, I suppose, is pretty simple: I read a lot, there are books all over the place, as you’ve seen, but maybe it’s not always so much reading as flipping and scanning, and I ask a lot of questions. I think I’m a pretty annoying person because I’m always asking questions, and looking around, signing up for things I don’t have time for, stumbling down the sidewalk with heavy, heavy books—once I did run into a lamppost, but it was because I was talking to someone, and the books jammed into my abdomen like you wouldn’t believe. I have all this material… I write some of it down, little bits and scraps of it—now I’m imagining Wittgenstein’s Zettel which was compiled after his death: these little scraps of paper in a box that editors threaded together into some kind of order (or it’s numbered, at least). I’ve got all this zettel, but in notebooks, not loose, that would be crazy. I write almost everything by hand, in pencil, in big, gridded notebooks. The notes are there, not in any kind of order, and I sort of… lock in, click on, look out the window, then it all turns, the notes forming these, like, topological shapes, merging and separating and cohering, and I start writing. It feels like a transmission. I am very calm. It does take patience. As I go, I might flip around, or get up and look at something and come back, but I pretty much just go until I can’t go anymore, which is maybe a couple of pages in the notebook. And then I do some moving and changing by hand, and then I type it later, and when I type, I add and revise. A lot of my writing is made from other stuff; I’m just the arranger of it. These other texts—their transcriptions, the act of transcribing: I suppose it’s like I’m putting something on, putting the information into my hand, from my eye to my hand then back up: I re-see it, re-see it in my mind somehow, and it comes out of my hand as something different, new. There’s magic in transforming information this way.

That’s just how it works. Making it fiction takes a little bit more on the revision and planning ends, like I might know before I get started that I want to render a particular scene. But that scene is made from a million other things, and I can’t ever predict what will come out, what shape it will ultimately take. There’s a high level of control; I’m very careful. At the same time, I feel like I’m doing nothing at all.

So the relation is that it’s all relational. And it’s all conceptual—maybe that’s also annoying, but it’s what interests me right now. The reference material that pulls me tends to be theoretical or philosophical, mostly as it relates to scientific or mathematical ideas. I look through a lot of textbooks, and I mostly read about things that have nothing to do with literature. Visual art and the physical world are also very important to me. I like to touch things, run around. I have a hard time sitting still, and I like to be outside. Etymology, history—I spend a lot of time on Wikipedia. I’ve written several pieces from the point of view of historical figures or objects. Marianne Moore might be standing just behind me, hand on my shoulder.

At the same time, as primarily a fiction writer, I’m a big daydreamer. There’s always some kind of little imaginary movie playing in my brain. I like to imagine, make things up, dream things up. I’m a terrible liar, but I’m good at making things up. I’m constantly staring out the window, or up into a corner of a room, everything slightly out of focus. What makes my work a little different is that sometimes these dreams have citations.

More specifically: No Measure came from a news article I read about a remediation project in the Gobi Desert. Math Class was more of a conceptual dare: I’ve got math, and I’ve got adolescence. If I kind of levitate ideas around those two things, let them hover in space, and then put them in a scene, like gym class, what happens? If I take complex mathematical thinking, like number theory, and I put it on a school uniform? With Math Class, I included a few source texts at the end of the book. Not all of them, of course. Just so you can see some of where I went. Well, that’s a bit of a lie. Some of the source texts I added later. I wanted to think about the relationality of disparate concepts, and I wanted to see what happened, maybe a bit alchemically, when I tagged a scene with something seemingly unrelated to it. I suppose they’re a bit like prompts. How do these things line up? Some of it is directly from my early notes, like the quotation from James Clerk Maxwell. I wanted to know about electricity, so I read about the history of electricity and credited what I read. For No Measure, though, I worked the same way, maybe even more so—it’s possible that No Measure is more referential than Math Class in terms of the amount of research I conducted and how much of the language in the book is found language… probably a very high percentage. But I didn’t include any sources. One reason for this is I didn’t keep track. I honestly couldn’t tell you where many of the transmissions came from, but there was a mess all over the floor, I’ll tell you that. The other reason is because I wanted the text to hang naked.

Why use reference materials, other information at all? Because I’m curious, because it’s fun. What happens to the texts after I use them? Their relation to me? I hope maybe they shimmer a little.

What does it all mean? Like, what does writing/making art mean for you in the larger context of your life? What keeps you coming back to it?

Kelly Krumrie: Impossible question. It’s my favorite thing, I can’t help it, I can’t explain it.

I love this interview. It makes me want to embody processes like these as well—to be this open to the influence of the world, and what is written about the world, on my own writing. It makes me want to give myself over to the processes that happen when I write, stepping aside from the processes that I want to force to take place.

Thank you so much to Kelly Krumrie for this infusion of joy and attention for our day. Don’t forget to check out her new book, No Measure, as well as Math Class, both from Calamari Archive.